David Brooks, summarizing the current state of happiness research:

The daily activity most injurious to happiness is commuting. According to one study, being married produces a psychic gain equivalent to more than $100,000 a year.

In other words, the best way to make yourself happy is to have a short commute and get married. I'm afraid science can't tell us very much about marriage so let's talk about commuting. A few years ago, the Swiss economists Bruno Frey and Alois Stutzer announced the discovery of a new human foible, which they called "the commuters paradox". They found that, when people are choosing where to live, they consistently underestimate the pain of a long commute. This leads people to mistakenly believe that the big house in the exurbs will make them happier, even though it might force them to drive an additional hour to work.

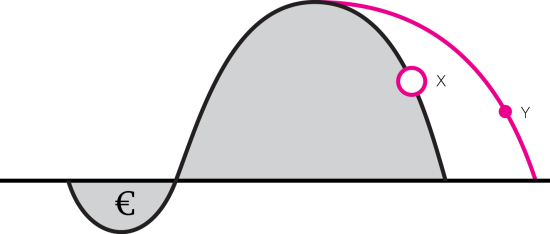

Of course, as Brooks notes, that time in traffic is torture, and the big house isn't worth it. According to the calculations of Frey and Stutzer, a person with a one-hour commute has to earn 40 percent more money to be as satisfied with life as someone who walks to the office. Another study, led by Daniel Kahneman and the economist Alan Krueger, surveyed nine hundred working women in Texas and found that commuting was, by far, the least pleasurable part of their day.

Why is traffic so unpleasant? One reason is that it's a painful ritual we never get used to - the flow of traffic is inherently unpredictable. As a result, we don't habituate to the suffering of rush hour. (Ironically, if traffic was always bad, and not just usually bad, it would be easier to deal with. So the commutes that really kill us are those rare days when the highways are clear.) As the Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert notes, "Driving in traffic is a different kind of hell every day."

But if commuting is so awful, then why are our commutes getting so much longer? (More than 3.5 million Americans spend more than three hours each day traveling to and from work.) In my book, I cite the speculative hypothesis of Ap Dijksterhuis, a psychologist at Radboud University in the Netherlands, who argues that long-distance commuters are victims of a "weighting mistake," a classic decision-making error in which we lose sight of the important variables:

Consider two housing options: a three bedroom apartment that is located in the middle of a city, with a ten minute commute time, or a five bedroom McMansion on the urban outskirts, with a forty-five minute commute. "People will think about this trade-off for a long time," Dijksterhuis says. "And most them will eventually choose the large house. After all, a third bathroom or extra bedroom is very important for when grandma and grandpa come over for Christmas, whereas driving two hours each day is really not that bad." What's interesting, Dijksterhuis says, is that the more time people spend deliberating, the more important that extra space becomes. They'll imagine all sorts of scenarios (a big birthday party, Thanksgiving dinner, another child) that will turn the suburban house into an absolute necessity. The pain of a lengthy commute, meanwhile, will seem less and less significant, at least when compared to the allure of an extra bathroom. But, as Dijksterhuis points out, that reasoning process is exactly backwards: "The additional bathroom is a completely superfluous asset for at least 362 or 363 days each year, whereas a long commute does become a burden after a while."

The same thing happens when we go car shopping. We tend to become fixated on quantifiable variables like horsepower (they're so easy to compare), while discounting factors, such as the cost of maintenance or the comfort of the seats, that will play a much more significant role in our satisfaction with the car over time. I'm always surprised when people brag about variables like torque or the speed with which the car can rocket from 0-60 mph. Who cares? I'd much rather spend 30 minutes testing out the front seat.

Update: Matthew Yglesias argues that the misery of commuting should lead to congestion pricing. I agree.

![]()